On Location With Peter Adams

AMERICAN ARTIST

July, 1997

ON LOCATION WITH PETER ADAMS

by Linda S. Price

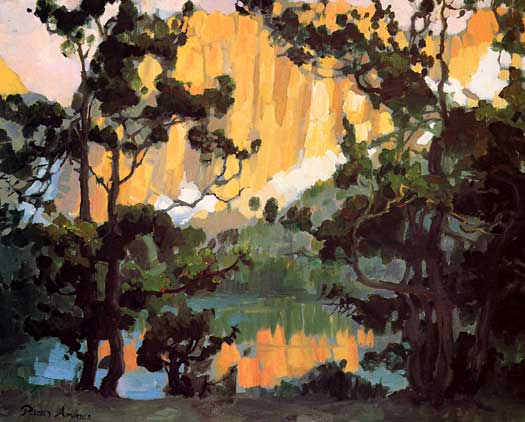

Reflection of Temple Crag, Sierra Nevada , 1996,

Reflection of Temple Crag, Sierra Nevada , 1996,

Oil on board, 18″ x 24″ Private collection

Adams executed this painting while on a two-week

backpacking excursion in the Sierras.

“When I started college, I said I wanted to learn to paint like an Old Master, but my art teachers thought I was crazy,” Peter Adams says. Even after college, when he began attending art classes at the Otis School of Art and Design in Los Angeles and the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, he had trouble finding traditional art instruction. Eventually, Adams enrolled in the Lukits Academy of Fine Art (now defunct) in Los Angeles and found exactly what he wanted. Studying under Theodore N. Lukits (1897-1992) not only gave Adams a classical art education but also introduced him to the early California painters, which led to what would become a longstanding interest in plein air painting.

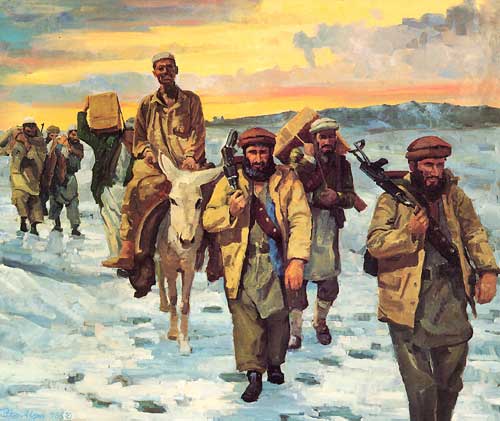

Although one of his favorite painting sites, the San Gabriel Mountains, is only a five-minute drive from his Pasadena home, Adams, who works on location in pastels, tempera, and oils, has painted in many more exotic locales. In the 1980s, he made two extensive trips to Asia, painting in India, Burma, Thailand, Hong Kong, the People’s Republic of China, Tibet, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bhutan. He even arranged in 1987 to be smuggled into Afghanistan by Moujahideen freedom fighters, not realizing that at the time there was a $10,000 Soviet bounty on Americans, dead or alive.

Afghanistan Supply Line, 1987, Oil on board, 48″ x 60″

Afghanistan Supply Line, 1987, Oil on board, 48″ x 60″

Adams spent two and a half weeks with the Moujahideen

shown in this painting. Here, they are carrying the ammunition

and medical supplies to Afghanistan.

Painting in remote locations led to memorable experiences. In India, many people had never seen an artist at work and referred to his painting as “making a photo.” Once, a merchant who felt Adams was stealing his customers’ attention destroyed his painting. In some areas of China the villagers were more interested in the hair on his arms than his paintings; they approached him quietly and gently blew on his arms to see the hairs wave. Bhutan, a tiny kingdom high in the Himalayas, was his favorite spot. “It’s a magical place,” he says, “probably because tourism is strictly limited. It’s the way I’d always thought of Shangri-la.”

During these travels Adams would average one small painting a day, either pastel, tempera, or watercolor. “It’s amazing,” he recalls, 14 some days I’d be traveling or sick, but I’d be gone for six months and come home with some one hundred eighty paintings.” (Many of these works he’d sell; others became the basis of larger paintings created later in the studio.) Obtaining art supplies posed a problem. He arranged for materials to be sent to him, but often they didn’t get through, and in India customs officials wanted to tax him $187 for $100 worth of merchandise! In China, he had better luck finding supplies, “especially,” he notes, “inexpensive brushes.”

Pictured is the artist in the lower left-hand corner in his Afghanistan desguise. (he had to dye his hair and beard to prevent being identified as an American and captured by bounty hunters for a $10,000 award offered by the Soviets.) He had just finished a painting of commander Malmud, who stands in front of several mujahideen. This photo was taken in Kunar Province,

Pictured is the artist in the lower left-hand corner in his Afghanistan desguise. (he had to dye his hair and beard to prevent being identified as an American and captured by bounty hunters for a $10,000 award offered by the Soviets.) He had just finished a painting of commander Malmud, who stands in front of several mujahideen. This photo was taken in Kunar Province,

Afghanistan, in October 1987.

At home in California, Adams likes to get up early in the morning and paint the sunrise. Often he will backpack into the nearby mountains accompanied by his four well-trained dogs-two Australian sheepdogs and two mutts. “Most of the paintings I show in galleries were probably started on location,” he says.

“A scene has to strike me and be interesting in terms of composition before I’ll paint it,” he adds. “I prefer a combination of sky, clouds, trees, and water. Even if the water is only a trickle, I feel it adds something important to a painting. At times I’ll look for the design in the trees. I also like to see a broad range of values, although sometimes I enjoy painting foggy scenes. But most of all, I like color. If a scene is hazy, I can make it even more colorful than it would be on a clear day because of the atmospheric light. An orange or purplish haze adds an element of mystery. The misty effects around a sunrise or sunset are especially intriguing to me.”

Painting these, dawn or dusk scenes can present problems, however. “Colors can be way off in some works I’ve seen,” he says. “Many times artists will use tones that are too dark or show the sun sort of popping out-it’s difficult to put the sun in and make it fit with the rest of the composition. I use as bright a palette as possible; I can always tone down the colors if necessary. I also try to anticipate what’s going to happen.”

Eucalyptus Spirit, 1996, Oil on board, 20″ x 24″

Eucalyptus Spirit, 1996, Oil on board, 20″ x 24″

“For instance, I make allowances for the sun turning redder as it sets.” In addition to painting sunrises and sunsets, Adams enjoys going out at night and painting statues illuminated from below with different colored lights. “This fascinates me,” he says. “It’s rarely been done before.”

Whatever his subject matter, Adams’s compositions reveal his interest in Far Eastern design. His paintings of trees, in particular, reflect his training in bonsai, the Japanese art of growing dwarfed trees in pots. “Oriental design,” he points out, “often involves large aesthetic shapes. A fog or cloud depicted in an Oriental painting is frequently a negative form. These areas, as well as those representing water, are left bare. I like using negative shapes in this way.”

Unless there is a great deal of drawing involved, Adams will begin a painting by sketching directly with a brush or pastel. At times, he says, he’ll paint a scene exactly as he sees it, with all the details. Other times he’ll make a lot of changes. “My field sketches tend to be less edited, and I finish ninety to ninety-five percent of a work outdoors. Once I take a painting back to my studio, I’ll work on it on and off for two or three days but make only subtle changes. In my studio paintings, on the other hand, I’m more apt to move I or reshape parts of the composition.”

When painting in oil in the field or studio, Adams uses the palette he has developed over many years: phthalocyanine green, a mixture of phthalocyanine green and cadmium yellow fight, cadmium yellow light, titanium white, cadmium yellow deep, cadmium orange, cadmium red light, quinacridone red, violet, ultramarine blue, plithalocyanine blue, five grays, and black. He also lays out a tint of each of these colors.

Adams tries to avoid blacks and browns (although he does keep a brown on his palette), admitting, “I don’t like them much. If I see something thats brownish, I’ll use broken color–maybe a blue and an orange so they mix visually. I have an aversion to paintings that are too dark. For me, many Old Master paintings rely too heavily on browns: They don’t give you a good sense of outdoor light.” Greens, so essential to a landscape painter, can also be a problem. “I set a mixture between phthalocyanine green and cadmium orange, which makes what I call ‘a dirty green,’” he explains. “Then I make a tint of it. I use this color more often than pure phthalocyanine green. One rarely sees a pure green in nature. The same thing is true for red–except for sunsets–or the planet Mars, or the red rocks in Sedona.”

Adams uses Dana oil paints that come in cans, and he puts them into small plastic jars organized by colors and tints. “Along with my palette, I store them in a special freezer, so they last forever,” he says. “But even out of the freezer they last for about a year. My medium is linseed oil.”

The artist is not particular about his brand of pastels. “Every year or two I go out and buy a bunch of pastels by different manufacturers,” he says. “I break them in half and store them by color and value in divided 35mm slide boxes.” For the most part he uses soft, rather than hard, pastels, and he works on Canson MiTeintes paper. He never sprays his paintings because fixative darkens the tones, and he claims he’s never had a problem with the colors coming off. Unlike some pastelists, he has no hesitation about occasionally rubbing in colors with his fingers. Working with both hands, he is careful to use different fingers for blending different values. “But I don’t want to give the impression I’m preaching,” he’s quick to point out. “My techniques are not the only ones; every artist has his or her own methods.”

Hopi Sunset, 1995, Oil on board, 20″ x 33″ Collection Mr. and Mrs. Don Wichmann

Hopi Sunset, 1995, Oil on board, 20″ x 33″ Collection Mr. and Mrs. Don Wichmann

Articulate and enthusiastic when it comes to the advantages of painting on location, Adams says, “First of all, I often have to hike to a site, so I know I’m getting exercise and doing something good for myself. At the end of the day I feel I’ve exercised hard, worked hard, and painted hard. When I see the work a few years later, I remember the thoughts I had while I was painting it and even the smells, and I can hear in my head the songs that were in vogue at the time. Working on location allows me to see subtle things that wouldn’t be noticed in a photo: for example, the shifting light and the shadows continually created by the clouds. I can add these changes to my painting as I’m working. Also, I feel a reverence and a closeness to nature I can’t experience in the studio. I’ve become much more familiar with the flora I’m painting; I can recognize the different types of sage, for instance. It’s given me a whole new perspective on nature. Painting outdoors also tends to make an artist more spiritual. It’s peaceful and relaxing when you’re out there alone. You have a sense of wholeness. ”

“Increasingly, I feel that I’m not in competition with other artists,” he goes on to say. “The older I get, the less I feel that competitive edge. Now I consider contemporary traditional painters the way I think of the great masters of the past: One is not better than another. Their art reflects their individual character. I believe there is a kindred spirit that links traditional artists. We have similar goals and fight for a similar cause. I think this bodes well for the future.”

Adams is president of the California Art Club and a signature member of the Pastel Society of America, the Oil Painters of America, and the Plein Air Painters of America. The American Society of Classical Realism recently named him an honorary associate emeritus guild member. He’s on the advisory board of the Academy of Art College in San Francisco and the art committee of the California Club in Los Angeles. In addition, he’s a member of the board of trustees of the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena. In California, the artist is represented by Galerie Gabrie in Pasadena, Joan Irvine Smith Fine Arts in Laguna Beach and San Juan Capistrano, Morseburg Galleries in Los Angeles, and California Heritage Gallery in San Francisco. He will be speaking at American Artist’s Art Methods & Materials Show, which will take place October 17 through 19 in Pasadena.

Linda S. Price is an artist, editor, and writer who lives on Long Island, New York.